Abject vessels: Laura Aguilar’s renegotiations of Chicana identity

Between two flags- an American and a Mexican one- a bare-chested woman is held captive: her body is bound by a thick cargo rope, snaking around the neck like a noose; her clenched fists tethered, pendulous breasts bulging over. Her head is hooded by a Mexican flag, whose key motif- an eagle devouring a serpent atop some prickly nopal- covers her face. Below the waist, she is wrapped in an American flag, half stripes, half stars. Born from the interstice between ostensible thesis and antithesis- between the U.S. and Mexico, subordination and desire, oppression and resistance- this is the mise-en-scene of Three Eagles Flying (1990), a photographic self-portrait by the late Chicana artist Laura Aguilar. A self-proclaimed fat, brown, dyslexic, working class lesbian, Aguilar chronicled her negotiations with the perpetual status of ‘Other’ over the span of a four decade career. Through an affirmation of this Otherness as well as celebrations of her chosen communities, the third-generation Mexican-American would carve out a unique representational arena of Chicanx identity, disavowing the restrictive categories- male, heterosexual and racially marked as mestizo- that conceive the default Chicanx body within and without the colonial imaginary.

In the growing scholarship surrounding Aguilar, this reading of her work has frequently been attributed to her earlier portraits of non-normative bodies- particularly Latina-identified queer women- often depicted in makeshift studios or otherwise enclosed spaces. Scholarship on her later work, from the mid-1990s onward- which saw a shift to nude self-portraiture in natural settings- appears to occupy a different discursive space altogether. While her formative portraiture works are construed as depicting her multiply situated Chicana intersubjectivity, series such as Grounded are tethered to the language and logic of a depoliticized spiritual healing, cast as a yearning for oneness with nature, the ‘benevolent’ mother. Without discounting the richness of existing readings, I contend that such a divide in scholarship ultimately does a disservice to both the artist and her work; it not merely fails to account for the legacies of colonialism intimately tied to the land and the body in her work, but also struggles to capture Aguilar’s intersectional experience of ‘otherness’ that is greater than the sum of its parts. What seems to be missing from this historiography is a theoretical engagement with the full breadth of her work, one that reads individual works intertextually rather than in isolated contexts, tracing their continuities as well as divergences. In light of this, I propose that we attend to Aguilar’s varied conceptual, material and narrative foci as participating in a wider terrain of contestation that exceeds the dichotomies of nature/culture, personal/political and private/public. To this end, this essay examines two works by Aguilar, Three Eagles Flying (1990) and Grounded #114 (2006), which, produced nearly two decades apart and with differing aesthetics, are underpinned by their participation in a wider project of healing and reclamation, for an individual whose humanity was contested on multiple fronts. Drawing primarily on philosopher-poet Gloria Anzaldúa’s corporeal theory of mestiza consciousness, I contend that Aguilar, through a psychic and visual interplay between various dualistic hegemonic paradigms- particularly of the US-Mexico borderlands- forged a hybridized arena of representation for the fat, lesbian, Chicana subject. My examination of Aguilar’s negotiations with Chicanx identity necessarily lies at the intersection of multiple critical approaches: disability studies, queer theory, women of colour feminisms, and postcolonialism, as they intersect with Chicanx studies.

“Has the queer ever been human?”, ask Dana Luciano and Mel Y. Chen in their post-anthropocentric analysis of Aguilar’s work. Better yet, I put forward, has the queer, disabled, fat, brown, working-class female ever been human? At the crossroads of these various social identifications, one locates the complex intersubjectivity that Laura Aguilar would articulate intimately through her work. Born in 1959 in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles, Aguilar was the daughter of a Mexican-American father and a Mexican-Irish mother. From the outset, Aguilar was endowed with a kind of double consciousness, oscillating between two competing poles of cultural identity- the American and the Mexican ones. Never quite in reach of the respectability that would grant her inclusion to either, her body was marked by two symbolic orders that clash and concentrate at the greater US-Mexico borderlands. Struggles with clinical depression, body image and auditory dyslexia- a disability that went undiagnosed till her 20s- further marked her early years with a profound self-loathing: “For as long as I can remember”, the artist recalls in her video work The Body 2 (1995), “I have always thought I should be dead.” All the same, it was in the face of these adversities that she would harness her resilience and power, undertaking a decades-long practice rooted in the politics of self-preservation (Harris, 2021).

Aguilar, L. (1990). Three Eagles Flying. [Gelatin silver print] Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/338340/laura-aguilar-three-eagles-flying-american-1990/ [Accessed 1 Dec. 2021].

At once, Aguilar’s work testifies to an anxiety about the incoherence of the self, forging a multiply situated yet still “authentic” voice for various oppressed groups, and also exuberantly gestures to the dissolution of any essential, codifiable notion of identity. These anxieties seep through in their most pronounced form in the aforementioned triptych, Three Eagles Flying, wherein Aguilar depicts herself bound by thick rope, the semi-nude, fat body flanked by photographs of an American flag, on the left, and a Mexican flag, on the right. Its formal composition is compact and symmetrical; each emblem’s weight is distributed uniformly and arranged with intention, such that the scene is saddled with a ceremonial, stiffly bureaucratic air. It is an image that rouses a gnawing unease, for it speaks the language of the unconscious; it presents itself at once as “dream, as fantasy scenario, and as a series of desires and identifications that follow no politically prescribed direction” (Calvo, 2005, p. 208). And in a literal sense, it speaks to the unspeakable: Aguilar’s inability to verbally articulate her cultural identity, by reason of her auditory dyslexia, as well as her limited proficiency in both English and Spanish. In the first instance then, Three Eagles Flying may be read as a scene of subordination, namely that of the Chicana subject; her hands and neck tied by a thick, nooselike rope, Aguilar is held captive by two symbolic orders, with no place to call ‘home’ in either. In this scene, the flags- supposedly transparent signifiers of national identity- serve not to secure any authenticity in the Chicana subject so much as compelling the artist to posit herself “in a performance of cross-cultural representations, separated from the absolute authority of both nations” but nonetheless marked by the complex matrices of state power and the cultural logics that undergird it (Arrizón, 2006, p. 66). The abject states of Aguilar’s body- queer, fat and brown- render her body at once a spectacle and a secret, a body outlawed within the colonial imaginary as well as in the Chicano nationalist one.

In the field of Chicanx studies, Aguilar may be read as participating in a genealogy of postcolonial Chicana feminisms that sought to negotiate alternative Chicanx subjectivities in the shadow of the male-dominated Chicano Movement [El Movimiento]. In order to advance la causa, “the agenda of self determination and empowerment integral to the Chicano Movement,” two political programs- El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán and El Plan de Santa Barbára- were constituted. The former mobilised the people to establish a Chicano “homeland” or Aztlán, whereas the latter sought to bring forward the study of Mexican heritage into the academy. Central to both endeavors was the reclamation of the term ‘Chicano’; in so doing, the movement sought to establish unity along lines of an undifferentiated ethnic and cultural identity, by means of distinguishing themselves from Mexican-American assimilationists. Constructed as a monolithic and unitary narrative of origin, the security of El Movimiento fundamentally relied on actualizing a series of binary oppositions: “a racialized class of Chicano colonized versus a superordinate class of Anglo colonizers; Chicano activists versus Mexican-American assimilationists; and Chicana loyalists versus Chicana feminists” (Segura, 2001, p. 542-43). The latter is of particular interest here; despite being cast as ‘vendidas’ (sell-outs) among their own groups, the 1970s onward saw a burgeoning proliferation of rich scholarship and activism by Chicana lesbians, cultivating a new discourse of Chicanx identity that would refigure “an alternative genealogy of the the revolutionary participation by shifting the historical imaginary of the Chicano movement.” Under the enduring legacies of American imperialism and El Movimiento, Aguilar’s non-normative body at once challenges the fragile conception of a healthy national body (by virtue of her disability), and imperils national unity in her claims to socio-political rights and visibility as a queer person. That is not to say that these identifications operate as mutually exclusive categories of experience; rather it is at their intersection that the abject Other of Chicano nationalist discourse as well as US imperialism is conceived. As per Julie A. Minich, the image of the nation as a “whole, nondisabled body”- whose coherence and ‘health’ is sustained through the exclusion of “external pollutants”- justifies the political marginalization of not only immigrants but citizens marked by disability, race and queerness (2014, p. 2). The categorical stability of both nation-states between which Aguilar is confined, then, relies precisely on the exclusion of bodies like Aguilar’s, such that they are ever haunted by the mutually-constituted and necessarily excluded Other. Such conditions give rise to the existence of what Mae Ngai calls “alien citizens,” persons who are “citizens by virtue of their birth...but presumed to be foreign” (2004, p. 2).

It is imperative to underscore, however, that Three Eagles Flying signals not a wholesale disavowal of the Chicanx identity, so much as a disidentification with and reconfiguration of the ‘Chicana’ category. In fact, through her growing affiliations with the Latina lesbian community in East L.A., Aguilar came to identify increasingly with the Chicana as well as mestiza identity, both of which are inherently political categories. In a geopolitical context then, Three Eagles Flying may be best understood, to paraphrase Gloria Anzaldúa, as a form of Chicanx border art that contests and subverts U.S. imperialism and combats assimilation by either the US and Mexico, but nonetheless expresses affinities to both (2015, p. 59). Therefore, this is not a scene of pure subordination; following Luz Calvo, if the analysis of Three Eagles Flying is circumscribed to its geopolitical footing, we imagine the Chicana subject to possess “no desire except to escape, an impossible desire” (2005, p. 212). I turn my attention back to the semiotics imbued in Three Eagles Flying: note the confluence of the Spanish word for eagle- “águila”- and the artist’s surname, Aguilar; and yet, as Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano notes, of the three eagles- the Mexican “águila”, the eagle of US imperialism, and Aguilar herself- none are flying (1997, p. 286). The águila on the Mexican flag that literally replaces the artist’s face, however, might suggest otherwise; indeed, the Chicana subject is unable to “look back” at the spectator of this image, but she is nonetheless endowed with the sharp vision of the eagle (Calvo, 2005, p. 210). Through this sharp vision, Aguilar’s radical intersubjectivity takes flight, what Macarena Gómez-Barris terms a mode of “heterogeneous seeing” that emerges from the liminal interstice between nation-states, cultures and borders (2017, p. 80). I extend on Chiara Mannarino’s interpretation of the Chicana subject in Three Eagles Flying as recalling Coatlicue, Aztec goddess of both creation and destruction, who is frequently depicted as a figure with “pendulous breasts, a skirt and belt of poisonous rattlesnakes,” and most notably, an eagle-feathered headdress (Mannarino, 2021). Within Chicana lesbian scholarship, the symbol of the Aztec goddess immediately conjures Anzaldúa’s theory of Coatlicue states; in its occupation of psychic, geopolitical and cultural boundary states, the conception of mestiza consciousness through Coatlicue points to its need to continually dissolve and reform such that it remains cognitively agile, for “rigidity means death”. Aguilar died of the same complications with diabetes that took Anzaldúa, both all too soon. It is a coincidence beset with tragedy, but also possesses a kind of poetry. I locate in these resonances between two radical bedfellows an ‘unspoken’ dialogue through which they co-authored a new mestiza consciousness, summoning Coatlicue in a transcendence of binary oppositions, fusing ‘here’ with ‘there’, birth with death, loving with mourning.

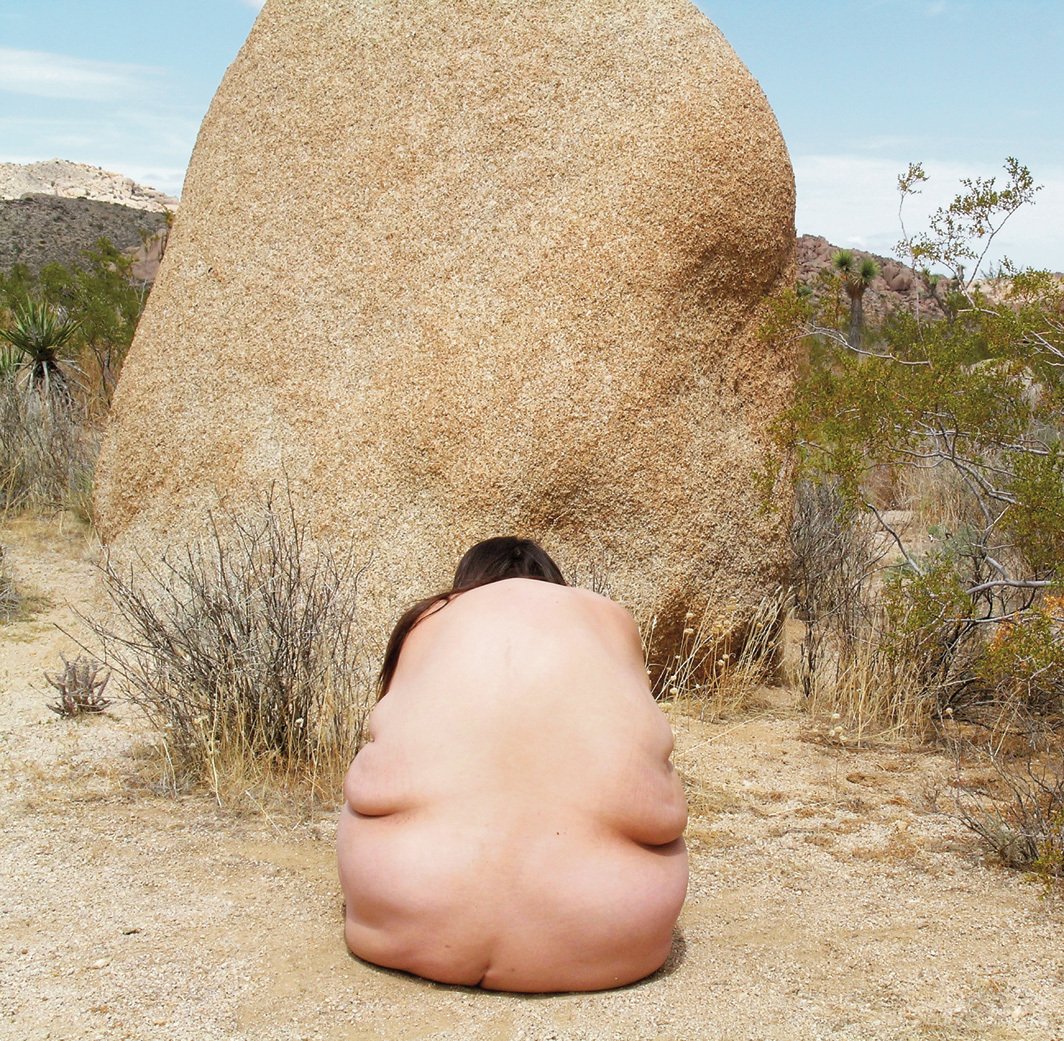

Aguilar, L. (2006). Grounded #114. [Ink-jet print] Available at: https://static.frieze.com/files/inline-images/editorial-30-lauraaguliar-grounded111-2006.jpeg [Accessed 3 Dec. 2021].

At once a scene of revolution and respite, of stillness and motion, familiarity and strangeness, Grounded #114 (2006) enters into dialogue with Three Eagles Flying, some two decades later, in ways that may not be conspicuous at first. In fact, what is discernible at first glance is the larger background object, a boulder: gritty, rough textured, sand coloured, surrounded by blue sky. Distinguishing the figure in the foreground, however, proves to be more challenging. It simultaneously resembles and differs from the boulder; they share asymmetrically oval contours, but the foregrounded figure is smoother in texture, supple, like human skin. One notices the hair on top and the cleft of the buttocks below, and gradually, a human form comes into sight. The self-portrait is a part of the landscape photography series, Grounded, comprising dozens of photographs taken within the El Malpais National Monument and Gila Mountains of New Mexico and the Mojave Desert of California (Gómez-Barris, 2017, p. 80). In this particular work, Aguilar’s body is contracted, with its limbs tucked away, mimicking the mighty, spheroid rock formation standing before her in Joshua Tree National Park. Facing away from the viewer, Aguilar’s pose visually obscures her sex, race, gender and age, and even makes her status as human difficult to discern at first Her averted gaze can be read in the tradition of feminist self-portraiture, wherein the female body refuses either to present itself as object of the male gaze or to “open itself to appropriation by the viewer” (Luciano and Chen, 2015, p. 184). Above all, however, it is the means by which Aguilar performs this refusal that saturates the work with multiple and even contesting meanings. As opposed to reinforcing her status as the self-determining subject of the image, she enacts a decisive turn away from “the demand for recognition within the circle of humanity” (Luciano and Chen, 2015, p. 184). What is considered, in the colonial imaginary, to be a trespassing body- Aguilar’s brown, queer and fat body, to be precise- is now given ground, finding both revolution and respite in an identification with more-than-human matter.

Between the bulging and dimpled contours of Aguilar’s form and the boulder lies an undercurrent of intimacy, a shared identification that transgresses the parameters of human and nonhuman, nature and culture, subject and object. By situating her mestiza body on land once relegated to terra nullius, and subsequently occupied, this sensual intimacy not only recalls but resists the violent histories of Spanish colonialism, American colonisation and the rampant settler practices that constituted the “American West”. This determined alignment between human and nonhuman, then, could signal a mode of decolonisation; that is, by virtue of Aguilar’s inclusion of her own mixed-race corporeality in the landscape, this is a scene that visually attests to the “histories of racial mixing, the logic of mestizaje, and the extensive networks of tribal communities,” ultimately expanding the category of ‘Chicanx’ (Gómez-Barris, 2017, p. 82). In the displacement of the Human from the (visual) hierarchical apex, Aguilar presents her body as porous, plural and fragmented, always entangled in a reciprocal dialogue with an equally agential material world. That being said, in reading Grounded #114 through a post-anthropocentric lens, I do not seek to negate or marginalise concerns relating to Aguilar’s identity, but quite the opposite. By relinquishing the notion of Human as superspecies, as sole sovereign- a designation whose seeds run deep in Enlightenment humanist thought- Aguilar assumes an expanded conception of the self as linked to the land, not just symbolically but materially. And despite her deep ancestral lineage in the American Southwest, the photograph’s location, Aguilar’s call for ‘groundedness’ possesses a heightened vigilance to sweeping claims of autochthony, instead invoking Anzaldua’s conception of a fluid ‘mestiza’ consciousness that transgresses bodily boundaries (Venegas, 2018). In the “1,950 mile-long wound” that is the US-Mexico borderlands, Aguilar forges a radical Chicana intersubjectivity through the interplay between oppression and resistance, what literary theorist María Lugones describes “as the possibility of resistance revealed in the perceiving of the self in the process of being oppressed as another face of the self in the process of resisting oppression.” In this sense, Grounded #114, created some two decades later, subtly answers to the fragmented Chicana subject in Three Eagles Flying by emerging as a whole and abundant subject in spite of and by virtue of these fragmentations.

In the accompanying text to a portrait from her Latina Lesbians series, Aguilar wrote: “I’m not comfortable with the word Lesbian but as each day go’s [sic] by I’m more and more comfortable with the word LAURA. I know some people see me as very childlike and naive. Maybe so. I am. But I will be damned if I let this part of me die.” Through these musings, Aguilar set forth a radically candid manifesto that attests concisely to the quiet insurrection that was her four decade career. My intention in reading Three Eagles Flying and Grounded #114 intertextually has not been to enforce a streamlined linearity into Aguilar’s work, so much as to underscore the personal and conceptual maturation that her artistic corpus chronicles. Amongst these two works, as well as many others I have not been able to touch on here, Aguilar spoke to an ostensibly simple project of self-preservation, which, to paraphrase Audre Lorde, stood in its own right as an act of political warfare when contextualised. Even as Aguilar’s work overflows the denotation of “Chicana feminism”, it nonetheless remains deeply Chicana and feminist in its connotations: feminist, in her search for agency in a body that is always-already marked by race, sexuality, gender and size, and “Chicana feminist” in her insistence on Chicana cultural lineage and authority for politically disenfranchised subject positions (Bost, 2008, p. 361). And as Chela Sandoval reminds us, “Chicano/a (like the label feminist, Marxist, capitalist, socialist and so on) is a political term,” not merely an identity (2002, p. 141). At the zenith of her career, demonstrating both alterities and affirmations of this Chicana identity, Aguilar was able to break into an unabashed exploration of the joy, pain and ultimate wholeness that persists even at these perpetual boundary states.

Works cited

Anzaldúa, G. and Keating, A. (2015). Light in the Dark (Luz En Lo Oscuro): Rewriting identity, spirituality, reality. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, pp.56–59.

Arrizón, A. (2006). Queering Mestizaje: Transculturation and Performance. Ann Arbor: University Of Michigan Press, pp.64–66. Bost, S. (2008). From Race/Sex/Etc. to Glucose, Feeding Tube, and Mourning: The Shifting Matter of Chicana Feminism. In: S.

Alaimo and S.J. Hekman, eds., Material Feminisms. Bloomington, In: Indiana University Press, pp.361–365.

Calvo, L. (2005). Embodied at the Shrine of Cultural Disjuncture. In: A. Davis and N.X.M. Tadiar, eds., Beyond the Frame: Women of Color and Visual Representation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.208–212.

Gómez-Barris, M. (2017). Mestiza Cultural Memory: The Self Ecologies of Laura Aguilar. Laura Aguilar Retrospective Catalogue, pp.80–83.

Harris, U. (2021). Looking Back on Laura Aguilar’s Pioneering Vision. Frieze. Available at: https://www.frieze.com/article/laura-aguilar-show-and-tell-2021-review [Accessed 1 Dec. 2021].

Luciano, D. and Chen, M.Y. (2015). Has the Queer Ever Been Human? GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 21(2-3), pp.183–190.

Mannarino, C. (2021). Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell. Burlington Contemporary. Available at: https://contemporary.burlington.org.uk/reviews/reviews/laura-aguilar-show-and-tell [Accessed 2 Dec. 2021].

Minich, J.A. (2014). Accessible Citizenships: Disability, Nation, and the Cultural Politics of Greater Mexico. Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple Univ. Press, pp.2–5.

Ngai, M.M. (2004). Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. [online] Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp.2–10. Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Impossible_Subjects/x2OYDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1 [Accessed 5 Dec. 2021].

Sandoval, C. and Davalos, K. (2002). Roundtable on the State of Chicana/o Studies. Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies, 27(2), p.141.

Segura, D.A. (2001). Challenging the Chicano Text: Toward a More Inclusive Contemporary Causa. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, [online] 26(2), pp.541–545. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3175454 [Accessed 3 Dec. 2021].

Venegas, S. (2018). Connected to the Land: the Work of Laura Aguilar. [online] KCET. Available at: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/connected-to-the-land-the-work-of-laura-aguilar [Accessed 1 Dec. 2021].

Yarbro-Bejarano, Y. (1997). Laying it Bare: The Queer/Colored Body in Photography by Laura Aguilar. In: C. Trujillo, ed., Living Chicana Theory. Berkeley, Calif.: Third Woman Press, pp.284–286.